The Meaning of Home in Covid Times: Part Three

Georgina Downey is an art historian who has published widely on the domestic interior in art. She has received an Australian Academy of the Humanities Travel Grant (2006) and University of Adelaide small research grants. Her most recent books are Domestic Interiors: Representing Home from the Victorians to the Moderns, (2013) and Designing the French Interior: The Modern Home and Mass Media (edited with Anca Lasc and Mark Taylor 2015) both published by Bloomsbury. Her third book, Domesticity under Siege: When home isn’t safe [due 2021] with co-editors Professor Mark Taylor, and Dr Terry Meade, is under contract.

Today I’d like to look at the art of internment as it reflects our own current experiences. I hope that the process of re-seeing these images following will help sustain our morale and give us all, now also temporarily quarantined some ideas about how home might be made sustaining and how it might be used to create the inner worlds so necessary now.

We’re being advised under Covid quarantine to spend at least some of the day doing something creative; to pick up projects laid aside maybe due to ‘lack of time’. Artistic and creative tasks and pursuits are often turned to, in order to make sense of enforced inactivity – they are a means of travel both imaginatively and visually.

Thus we explore the work of Paul Dubotzki, a World War 1 ‘enemy alien’ – a German-born expatriate in Australia. This man, a photographer by profession before his arrival, recorded his experiences of three Australian internee camps, Torrens Island in South Australia, and Holsworthy, then finally Trial Bay, in New South Wales.

His photographic works give us a vivid account of life in internment and form the core of the The Enemy at Home, an online exhibition that showed at the Museum of Sydney in 2011. The curators sourced the works by tracing him back to Germany, where his cache of works were uncovered. Thus little was known about him until recently.

For us the Dubotzki’s camp photographs form an intimate picture of the difficulties of creating home under confinement. While different in many respects, the ‘enemy aliens’ in Australia during World War One endured some similarities of experience with our own. Theirs was an ‘open-ended’ confinement time-wise; they didn’t know how long they would be locked up.

Additionally, and like ours, the internment of the German born held no obvious association with a crime or misdemeanor. Dubotzki and his fellow German born internees (men, women, and children) were locked in camps for the reason that their presence in the community, while Australia was at war with Germany, was — in an almost virus-like sense, an ‘opportunity’ for them as loyal Germans to spread lies and propaganda, and generally to undermine Australia’s war efforts. They therefore needed to be ‘contained’. Some German South Australians, like Hans Heysen, avoided internment, but many didn’t and were placed in camps that didn’t ‘open’ until the end of the war.

Dubotzki was born in Munich. He arrived in Adelaide in 1913 aged twenty-two after working in South East Asia as a photographer. He settled in Rundle Street, and carried on his photography trade, but after only a year was imprisoned as an ‘enemy alien’ at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Dubotzki’s time at the Torrens Island camp was difficult, as it was for all the men there. Torrens Island, adjacent to Port Adelaide, and near Outer Harbor and now the site of a major power plant, had originally been used to quarantine new settlers, arriving by sea of course and possibly carrying tuberculosis, and other diseases from Home. However in 1914, official preparations to turn it into an internment camp were inadequate, and the internees had to create their own camp out canvas tents. Conditions were cramped and unhealthy, yet Dutozki’s photos show the men ‘making home’ as best they could.

Torrens Island c. 1914. Paul Dubotzki

Steamy in the summer and freezing in winter, it would have been a terribly hard life in the Camp. The photo above shows seven young Torrens Island Camp internees, including the photographer himself, (top middle) at the opening of a tent. Carefully posed to fill the space, the men are wearing a strange assortment of clothing that makes gauging the season difficult.

It could be summer, or so we might think from the bare chests of three, or maybe they’ve been doing manual labour. Is the man in the coat cold, or is he suffering from malaria, that was a huge problem on the Island? While they’re young and fit, the range of expressions on their faces tells the tale of the toll of imprisonment. Along a spectrum from cheeky to resigned, they look out at the viewer as if trying to reconcile themselves to the harsh hand fortune and Fate has dealt them.

Dubotzki’s other photographs of Torrens Island camp captured the camp’s appalling conditions and the abuses committed by Australian guards. Some of these were later submitted as evidence in official protests and a Defence Department inquiry.

In 1915 Dubotzki was transferred to Holsworthy Camp and then to Trial Bay, both in New South Wales. The latter camp was on a headland with a single access road and comprised a jail and outbuildings stretching down to the beach. Trial Bay was an ‘elite’ camp; and among the internees were professionals, academics, businessmen and the German Consuls from New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia.

Here, the internees had the most privileges, including a prisoner’s committee through which they could negotiate with the Australian Army who had charge of the camp. Dubotzki’s photos reflect how at Trial Bay the internees worked together to construct what was essentially a fully functional ‘village, with its own street signs, and even a daily newspaper. The men built a coffee shop, a theatre (in which they made their own elaborate costumes and sets, and the womens’ roles were played by men), a bakery, and a blacksmiths. Sporting clubs offered boxing and athletics. An early ‘adult learning centre’ for languages and other subjects was set up. Dubotzki himself set up a small business selling prints of his photographs to his fellow internees.

Even so, life at Trial Bay was tough. This 1918 diary entry by an internee could almost have been a Facebook post from yesterday about being confined at home during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Causes for friction are popping up everywhere and you have to pull yourself together all the time in order to avoid confrontations. Things get easily out of dimension and people become irritable and touchy due to the long imprisonment. You just can’t avoid it. Some days the mood is following the course of the war, one day there’s high tension and then again one is doomed to wait and wait.

W. Daehne, Diary entry Sunday 21 April 1918, ML MSS 261/3 Item 18.

What is striking to me in the few interior images we have is how organised the spaces are; reflecting how the internees used all their pent up energy and determination to ‘make home’ in the open ended ‘crisis’ in which they found themselves.

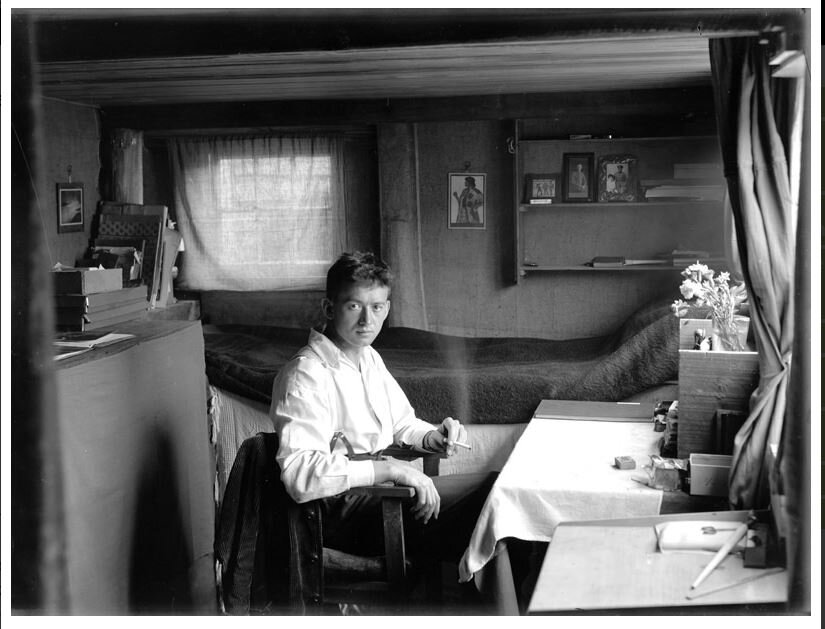

This beautiful portrait shows the photographer himself ‘at home’ in his hut.

Muslin curtains soften the light from the back window, and Dubotzki turns three quarter profile to the camera his features softly illuminated by the window over his desk. Our eye pours over the neat ‘ship shape’ interior, the carefully pulled bedspread, the spare bookcase, a framed art print on the wall, and comes to rest on the curiously pristine white table cloth that covers the desk. It reads as ‘blankness’ the blankness of days for a young man imprisoned for nearly five years for no crime except for having come to Australia from Bavaria.

The poignancy, (or ‘punctum’ – the emotional punch from a photograph detail, as Roland Barthes described) for me comes in this image from the freesias at the window sill. I see these as a heart-breakingly powerful symbol of Dubotzki’s simple human response to the beauty of natural things, and his use of fresh flowers as interior decoration as an indefatigable sign of his optimism, his capacity to ‘meet’ every day, and as an important means of seeing himself through years of incarceration.

A similar determined recourse to ‘normalcy’ to taste and the maintenance of the habits of home as a form of optimism, is also evidenced here in this above work by Dubotzki depicting fellow internees gathered in the private quarters of one in the group.

The room’s owner -- mostly likely the man reclining in the back corner on a stretcher -- has repurposed the v-shaped wooden wall braces to form a small library, and picture display area. To the left, he has hung photos in a symmetric display. Shelves are swathed in embroidered material, curtains have been placed, and the men sit in quiet comraderie, each with their newspapers and books, a bottle of beer on the table.

Along with some 7000 other German ‘enemy aliens’ Dubotzki was repatriated to Germany in 1919. Once there he married, and carried on working as a photographer and artist in Dorfen. He had three children, and it was contact with two of his now elderly daughters that led curators to discovering this cache of images from his time in Australia.

Some of his prints are held by the Migration Museum here, and the remainder, and his glass negatives and cameras, remain with his family. His photographic record of the camps, are vivid, humanist and of remarkable quality, and they show us in detail how he and his fellow internees ‘made home’ as a crucial part of their management of their day to day life in Australian prison camps.

My next posting for Part Four of ‘The Meaning of Home in Covid Times’ will explore the remarkable works of Charlotte Salomon, made during confinement when she was interned with her family for being Jewish in Southern France in WW2. Salomon was found and sent to Auschwitz in 1943, where she was murdered by the Nazis aged only twenty-six. The works she left behind leave a permanent record of her experience.